1. I return to the Practice of Goodness as one returns to the arms of a long-desired lover. With relief, and a sense that I have always belonged here, and the separation has been harder than I could ever let myself know until it was over.

I have written on my blog No Place for Sheep in the pages Infidelity and the category Adultery of my affair with a married man.

This affair disturbed me so deeply I decided to seek help to deal with its aftermath. The Book of Longing, a title I’ve borrowed from Leonard Cohen, is my record of discovery.

I am tired of the superficial. We love, we hurt, we ache, we desire, we rage, we suffer and yet we speak to each other mostly of the banalities of life on earth, enduring the rest in silence.

The deeps are what draw me. The mysteries. The things concealed and unspoken. These are what I will give voice to as best I can.

There’s no chronological order to be found here. The flow of eternity does not adapt itself to the demands of time, and what happens in the places we call our hearts and spirits has little to do with time, and everything to do with eternity.

ƒ

I met him, my lover, only because he was ill, suffering from the same cancer I suffer, though I was in remission and he was at the end of a gruelling cycle of chemotherapy. We’d known each other for a couple of years in cyberspace, sharing the same politically-minded community and interests, admiring one another’s writing. When I was visiting his area I suggested we meet for coffee, as I wanted to give encouragement and companionship to someone I liked, who was enduring one of life’s worst experiences.

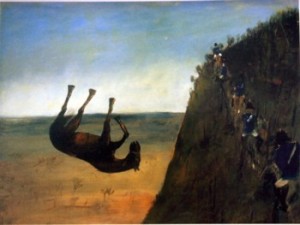

We agreed to meet in the Nolan room at the National Gallery. The painting that impressed itself upon me most that morning was the horse falling upside down off a cliff. I didn’t know why at the time. But later it came to signify my own state of mind.

My husband, about whom I’ve also written on No Place for Sheep, had some time earlier suffered a massive stroke that left him paralysed on the right side of his body, without coherent speech, completely dependent and in a nursing home. Not long before I met the man who was to become my lover, I’d spent several months by my husband’s bedside.

During this time of witnessing, I had a most extraordinary experience. Each time I visited and settled myself beside his bed I felt a strange sensation that was physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual, though I am not quite sure of the meaning of that last term as I have no religious belief. Perhaps metaphysical would serve better.

The sensation as I can best describe it was one of intense love and compassion, unlike anything I have ever felt before, and requiring no response from him, which was just as well as he could give none. This sensation was self-renewing: the more I allowed myself to experience it, the more it flooded into me, and through me to him.

On its path the strange energy nurtured and strengthened me, and I was able to daily spend hours with him for what turned out to be months, without ever feeling exhausted. Other circumstances surrounding the situation exhausted me, but not being with him. I was able to give myself over completely to this extended experience, which was remarkable as my personality is not at all suited to the long periods of holistic stillness it demanded.

I was in an altered state. Even away from him, the altered state remained.

It was in this altered state that I suggested to the man who became my lover that we have coffee. Open, vulnerable, grief-stricken at the loss of my husband as I’d known him, yet in strong denial of all my sorrow and anger about what had been lost, I found another man fighting for his life, one who unlike my husband could respond and who, unlike my husband, could ask and give and love me back. He, I have no doubt, sensed in me the loving compassion that hadn’t left me, and his need of it was great.

And so we fell in love, at first sight, in the Nolan room in front of the painting of the falling horse. It was a coup de foudre. And neither of us knew the first thing to do about it.

We are eating lunch at an outdoor cafe in a southern city. It’s winter. I’m used to warmer climates and am wrapped in layers of clothing, up to my chin. He leans across the table, and strokes my face with his forefinger. I make a joke, and he taps me lightly on the side of my nose. Then he says, I love you. And then we look at one another and the look is fierce. He says, softly, you’re mine, and I say, softly, I know.

This is not something I could have imagined myself saying to a man, had I ever given the matter any thought. But I am overwhelmed by a rush of hot feeling that causes me to temporarily relinquish ownership of myself. He holds my gaze, he doesn’t flinch or blink, he holds me there in that unexpected and foreign desire. Remember, he says. We have done so many things today and every one of them is for us to remember. Yes?

Yes, I say.

The eroticism of surrender. It is new to me, at least to this extent.

He feels it also. He writes of how he wants me to fall on him while he lies helpless, and take whatever I want for as long as I want and I find it reassuring, the knowledge that this desire to yield is not confined to me. When he writes of his wish I feel in myself the thrill of domination, though it is tempered by discomfort: I am not used to taking what I want without considering the other. I wonder if I might feel silly, embarrassed, feasting on him while he lies still and unresponsive. I tell him this. Absolute honesty, he’s promised, and I’ve promised in return. No pretending. This is one of the things I love about you, he tells me. I know you will never pretend to feel something you don’t. Everything with you is real.

Ah, he writes, when I tell him of my fears. I will respond. But I won’t touch you. You’ll have to tie my hands so I can’t touch your breasts, otherwise I won’t be able to resist. And then you can lean over me and lower a nipple into my mouth and I will tongue and suck and feed. You will decide when to take your breast away from me, and when to give it back. I will beg. I know that. But you will decide.

ƒ

I’m weeping in the office of the man I’ve come to for help with myself. For the last ten days the right side of my body from my head to my foot, has been painfully seized up. It feels like structural damage.

I’ve been to this office four times now, and the moment I sit down I start to cry and then I continue to cry, pretty much for the next hour. Strange, apparently disconnected thoughts erupt through the weeping. I tell him about my right side, how it hurts.

Which side of your husband’s body was paralysed? he asks me.

The right side, I say, and then double over with anguish so bad I can barely breathe.

Yes, he says, kindly. Yes.

2. Him to Her

I can’t imagine my life without you

Nor mine without you

But what if something goes wrong?

I don’t ask him, what kind of something.

Our second meeting is in a cafe in a shopping centre. Our conversation is more personal, yet still I do not notice from him a word or gesture that signals any interest in me, other than that of a fellow-sufferer and geographically distant friend. I’m not looking and I’m not giving off any signals I’m aware of. The coup de foudre remains unacknowledged.

So when he puts his hand across the table, palm upward, inviting mine, and I without a second’s hesitation place mine, palm downward, in his, it is as if there has been an entire other conversation in progress of which I have been completely unaware, and during which it has been agreed that he will put out his hand for mine and I will respond to his offer as if it is the most natural thing for us to do. Which it isn’t, on the level on which we’ve been conversing, on that level it could be read as predatory, or presumptuous, or harassing, or just plain mistaken.

From that moment on we communicate almost entirely on the previously unacknowledged level, and when either of us deviates the other is distressed at the betrayal. He has never known this type of communication with a woman before, he tells me frequently, but for me it’s a language I’ve spoken most of my life. It’s the other one, the superficial, that is a foreign tongue to me, that I struggle to speak like a second language I never properly learned.

I want our thoughts to touch.

You are my last thought before I sleep, and my first thought when I wake.

And you mine. I fall asleep imaging the weight of your breast in the palm of my hand. In the night when I wake, you are there, and I am holding you, your back to me, my cock nestled between your thighs.

Our most banal communications come unmediated from this mysterious place, and when he writes or says, Listen, today I will be and you will be and the time will be so I will let you know and then you can… his tone, and mine, are so infused with the inexplicable power of a language that has no words, that even ordinary exchanges make his cock stir, and cause me without thought to spread my thighs as if to receive him.

This “psychic” sex is so real, today when we were interrupted my balls ached as if we had been physically together, and prevented from fucking. I want to be with you so badly it hurts. It hurts.

When first I see him he is naked everywhere, chemotherapy having robbed him of all adult concealment. I am astonished at his beauty, naked as a little boy yet grown, his vulnerability more stark than any I have ever seen. There is no other way to put it: I adore his nakedness. I kneel before his nakedness and take him gently in hands that love, without my interference, fills with tender strength. It is not too much to say I worship him.

I love how you look at my cock. I love how gently you touch him. Kiss him. Do you know how much I love how you do these things?

The loss of this form of communication when it comes, feels like death.

ƒ

I write tentatively about my adoration of my lover’s body. I don’t know if it is acceptable (to whom?) for me to confess to worshipping him. What I felt was not unlike the awe that overtook me when I gave birth to my babies and first saw their perfect bodies, but of another order: we came together as man and woman, not mother and child.

Although, and nothing is unambiguous nothing is straightforward in these matters, my lover asked to suckle from my breasts, asked if they were full for him, if I would feed him, nourish him, and when he asked this of me I felt them swell, and tingle with sensations I recall from when I heard my babies cry.

And he writes to me

I want to feed you also. I want you to take from me all the nourishment you need, from my cock. If I could I would feed you from my nipples, sometimes I imagine that I can. Remember, take everything you need. I will feed you.

ƒ

Throughout our affair I imagine myself in his situation. I imagine myself living with my husband while simultaneously being in thrall to somebody else. I imagine loving this other person and loving them loving me, all the while knowing I will leave them the moment I am caught in my duplicity.

I could not create with another what my lover creates with me, knowing I would leave him with what could only be anguish, to save the life I already have in place. We all have things for which we would not forgive ourselves. Mine, or one of them, would be to awaken such love in another, to beg for such love from another, all the while knowing I would leave at any moment, to save myself.

Even though I recognise in some dark corner of myself that I am horrified at my lover doing this at all, and worse, doing this to me, I stay.

What would you do if you were me?

I would never do what you have done. I would rather be alone forever than live as you are living.

So why do you love me then?

I don’t know.

And then I remember it was my husband I loved like this, adored, worshipped, longed for, reached for in the night, nourished from my breasts. There was no room for another lover in my mind and heart and body. And if illness and death had not robbed me of him, in my heart I would be there still.

I visited my husband. He reached for my breasts. I unbuttoned my shirt and leaned over him so he could touch them with his good hand. Then I lowered my nipple into his mouth and he suckled and wept and spoke to me in his incomprehensible language and then I laid down beside him and held him in my arms, his head against my naked breasts, until he fell asleep.

If you’d met me when your husband was well would you still have loved me?

No. I would have liked you. Been interested in you. But loved you like this? No.

ƒ

3. Some thoughts about how we are formed

When I was a child my life divided itself into two seven-year cycles, during which events occurred that could not have been predicted.

The first seven years I spent with grandparents who loved and nurtured me. Those were the golden years.

The second cycle of seven I spent with my mother and stepfather who neither loved nor nurtured me, and during those years I came to believe I had no autonomy, but that I existed only to be what they wanted me to be.

The third cycle, after escape from that dyad, was chaotic and filled with fear but it was the first two cycles that formed me, and influenced every aspect of my life.

There are schools of thought that insist our present is determined by our past and until we recognise this we are doomed to repeat it. The repetition compulsion, Freud named it, in which we are unconsciously compelled to re-stage our traumas in a desperate effort to this time, overcome them.

This thinking makes some sense to me. The past can hold us in place when the organism’s instinct is to progress. Why, then, would it be so surprising that we would set ourselves the task of re-enacting what imprisons us, with the goal of bending the past’s steel bars sufficient enough for us to crawl through them, to freedom?

ƒ

He writes, because I am uncertain: I will NEVER be “rejecting” you. NEVER. NEVER – do you understand? NEVER.

Thank you, my love, for this reassurance.

He asks me, when he is facing some unpleasant medical procedure, if I will give him an image he can think of to distract him from the experience. His favourite is of me suckling him, holding his head against my breast as he lies across my lap, stroking his forehead, his cheek, as he feeds.

I am at times his secret mother in our secret coupling.

This is surprising to me as I’ve never thought of myself as especially maternal.

But thinking myself un-maternal is inaccurate. What I wasn’t drawn to, and still resist, are the managerial expectations the word maternal implies. That I will “mother” in the sense of finding socks and knowing where everyone should be and when. All the mind-cluttering tasks people should, after a certain age, learn to do for themselves. There is little so crippling for either party than when one person unnecessarily takes entire responsibility for things another can do perfectly well.

I have always needed time to think. A woman’s need to think ought not to be routinely displaced by the imagined obligation to service the wants of others. This is not what is expected to happen when men need to think. This is not how men are expected to daily demonstrate their love.

I am anxious tonight, love. Give me an image I can go to sleep with.

Remember our tongues?

Oh yes, how fierce they were!

And how sweetly they loved one another?

Aaaah! Yes, I remember. Oh Lordy, how I remember! And how you trace the ridge between my balls with the tip of your tongue. So gentle. So loving.

I will sleep now, lovely lady. And you must too. Night night my love. And thank you.

ƒ

I only began to learn how to consciously comfort with my body when my husband became ill. Although I hoped his hardship was eased by my new skill I couldn’t be sure, as he had few ways of telling me.

I knew though, that he wanted my presence and assistance. When nurses brought his food he waved them away with his good hand, pointed at me and gabbled in his alien tongue. He would not accept feeding from anyone else. So I thought, he knows me, and he feels my love.

I spooned the infant nourishment into his mouth, opened like a baby bird for its parent’s beak. Gently, I wiped his beloved face. I remembered as I did so the times when he wept for some sorrow and I would lick up his tears, an animal mother cleaning up an offspring, and then we would laugh, and likely make love.

He was sometimes tender-hearted, and at that those times wept easily. Say Wednesday, he would laugh at himself, and a Jewish man will cry.

I didn’t fully realise the power of the body to comfort until my lover told me. Feeling my skin against his, remembering our bodies together, conjuring me up at his most testing moments. How my love, his love, our love soothed him as he struggled with procedures and their aftermath.

The moment he asked or wrote that he needed my body I responded as if it was the most natural thing, and my mind followed quickly with the few words required.

This is what human beings can do for one another, even when a thousand miles apart. With our bodies. With our minds. I never knew.

ƒ

In winter, my grandmother scrubbed me in the kitchen sink, while I looked out of the window at our snowy garden in the early evening light. Later I was tucked into a bed already warmed by a heated brick wrapped in flannel.

My aunt painted my small toenails a pearly pink, as she sat beside the kitchen stove attending to her own manicure.

My uncle carried me on his shoulders through the house, and my head almost touched the ceiling, so tall was he.

My grandfather took me in my pram to his working men’s club where he parked me in a corner and his friends fed me lemonade and crisps. More than once he drank too much and forgot me when the time came for him to walk home. Eventually, my grandmother would tolerate his forgetfulness no longer, and he was forbidden to take me on his outings with his friends. Instead, he wheeled me soberly around the park.

My father was unknown to me.

And I have no memories of my mother at this time.

ƒ

My lover’s wife (this is how she introduced herself to me when first we spoke, this is …’s wife) told me that after seeing an image of my husband she thought he looked a lot like hers.

I don’t know how to name this woman. I’m discomfited by referring to her as his wife, or the wife, or my lover’s wife, or Wife, as a universal. Neither can I bring myself to create a name for her, because then I will be creating a character who is in keeping with that name, and she will not be her.

I apologise for describing a woman as “his wife.”

I don’t know what his wife meant by remarking how physically alike our husbands seem to her to be. For to me, intimately knowing both men, there is no resemblance at all. Was she implying that it wasn’t really her husband I loved, but what I saw in him that reminded me of my own lost spouse?

I have careful compared the two men in every way. Except in the matter of their physical frailty and need for loving comfort, they couldn’t be more different.

If I was removed from the equation they probably would have liked each other.

A brilliant edginess (in the sense of the avant-garde) was my husband’s defining characteristic, the unique sensibility he brought to every thought, always unexpected, sometimes offensive, usually poetic.

Old girlfriends would visit, and tell me, I just want to have a bit of his mind, and I knew exactly what they meant and we would sit around our kitchen table drinking tea while he riffed, making great imaginative lunges between apparently disparate topics, for that was his interest, the connections between things, finding them, inventing them, describing them.

I think, when considering intelligence, it is more a matter of imaginative courage combined with learning. The intelligent and courageous imagination is a wondrous thing, especially when it is lived through the body as well as the mind and heart.

I know that had my husband loved another woman as my lover loved me he would not have kept it secret from me. I have no idea what the outcome of such revelation would have been, but I know he could not have loved another so deeply, and tried to live as if there was nothing different in his life and, necessarily, mine.

That is, perhaps, the biggest difference between the two.

ƒ

4. I knew, his wife told me. I knew from the beginning.

Why didn’t you say something to him? Why did you let it go on for so long?

Because, she said, I didn’t want to deal with it.

ƒ

By now I’d learned he’d had affairs for much of his marriage. But he’d never, she told me, done anything like he’d done with me. Fallen in love. Increasingly neglected her. Become obsessed, and withdrawn from his daily life.

He’s an honourable man, she protested. I know you don’t think so but he is.

I think, but don’t say, I know there are ways in which he is an honourable man. But if he were my husband, I wouldn’t be interested in those ways if he wasn’t honourable in his dealings with me. I would feel worse, that he took the trouble to be honourable in other areas of his life, but not with me. That hurt would make my soul ache for the rest of my life.

He is a man who cannot not watch a fly drown, without feeling compelled to save its wretched life. While saving the lives of flies he lies and dissembles and promises, and betrays her yet again.

Better to let a billion flies drown than that.

ƒ

I imagine a woman so exhausted by her husband’s infidelities she can’t deal with one more, even as it unfolds before her eyes. Even as it matures into deep love, and equally deep obsession. Even as he increasingly neglects her, and in her heart she knows the reason.

Why, I want to ask her, do you think so little of yourself that you admire him for his honourable stand towards others, while he dishonours you, and the marriage you’ve made with him?

There is power to be had in knowing things about another, things the other believes he is keeping from you. There is a grim satisfaction to be found in watching another believe he is deceiving you, and knowing all the while he is really deceiving himself. The art of deception finds many and complex expressions, between people who profess intimacy.

You have no secrets, though I will allow you to believe you do. Until I won’t allow it anymore.

What a hard and dead-end road she chose, if it ran in that grim direction.

More than anything, I wish I’d known his history.

ƒ

Towards the end of our affair he spoke to me of years of drunken fumblings, of awkward breakfasts with women he’d fucked the night before while his wife kept to their home and the children it then sheltered. Did you feel guilty, I asked him. Yes, he replied. Always.

You aren’t very grown up in some ways, are you?

I’ve always been wrapped in cotton wool, he replied with calm satisfaction, as if it was his due.

I gazed at him, taking in this revelation of male entitlement, the like of which I hadn’t in my personal life yet encountered. Women give him what he wants. It just is.

ƒ

I’ve never seen the purpose of guilt. It doesn’t stop a person doing something, as far as I can tell. It’s a useless emotion that careens around inside a head and stays there. There’s an idea that the capacity to feel guilt is a sign a person is, at heart, good, but surely the feeling is worse than nothing without an action, or the cessation of an action.

I watched him as with sideways looks he told me those things. For the first time I saw his mask slip. He was testing me, I knew, but he wasn’t my husband and never would be, so I didn’t care what he’d done. I laughed at him. I laughed at his admission to drunken fumblings and awkward breakfasts. What fun was there in that, I asked him. He shrugged.

I understood it was his rebellion. It was the act itself that temporarily liberated from whatever he felt imprisoned him, and not the quality of the experience that mattered. It was the freedom of unilateral action, a brief respite from the relentless mutuality of marriage.

He asked me if I, when an academic, had attended conferences and fucked like he did. I gave him two names he recognised who’d put the proposition, but I wasn’t interested in either of them that way, and politely declined. It wasn’t a moral thing, I told him. I had no need of liberation in that way. I only wanted my husband. Nobody could hold a candle to him, I said, singing the line from the country and western song because I knew he disliked country music and I knew too, that he loved me to tease him.

Would you have fucked me if we’d met like that? he asked, putting his hand gently over my mouth to stop my singing.

We’d never have met at a conference, I told him, my words thickened with desire as I spoke them through his fingers, now tracing the outline of my lips. Our disciplines are worlds apart.

ƒ

My husband was unfaithful once or twice, so I knew a little of how it could be. He never fell in love, and I know if he had that would be more than I could tolerate.

I felt many things. But I see now that one of the worst was how I came to regard the other woman as less than me. As someone unimportant he fucked and discarded, regardless of her feelings. I became complicit in the exploitation of another, relieved that she meant nothing to him.

The way that is said of another human being. She meant nothing to me.

She was an aberration we wanted gone, the better for us to “move on,” “move forward,” “repair our marriage,” and the rest of the bubblegum clichés infidelity experts on morning television prescribe, rapidly, in order to get as many in as possible before their allotted time runs out.

This is what in reality might be in store for a woman when her husband introduces betrayal into their union: it is impossible to live closely with a liar and exploiter, without in part becoming both.

My lover’s wife observed him as he lied, for going on two years. What did she feel as she watched through eyes jaundiced by decades of betrayal? Contempt? Superiority? Power? Exasperation? Rage? Grief? Exhaustion? Despair?

Why didn’t she say anything, I asked him when it all fell to pieces.

I don’t know. She probably thought it would pass.

All that time? She thought it would pass?

I’m cynical about men, she later told me.

ƒ

You made a choice, I hissed at her, my anger rising in reaction to her threat to prevent me writing what she described as intimate things all over the Internet. Nothing provokes me as much as a threat to silence me.

Every time he fucked another woman you had a decision to make, I snarled. Your decision was always to stay, move past it, put it behind you, focus on your marriage, whatever banal phrases you thought fitted the occasion and lent you the illusion of control. You decided to live a life of uncertainty with a man you knew betrayed you. He wasn’t holding you in place with violence and fear for your fucking life.

I knew I should never have let him meet you alone! she shouted.

A startling revelation of the depth of mistrust in which they lived their daily lives.

Later, I thought long on how a woman must be in relation to a man about whom she uses the words, I knew I should never have let him meet you alone. She should have policed his first meeting with a fellow writer in order to thwart his nascent stirrings of desire?

It was her failure that she hadn’t, and now all this had come to pass?

I should have stopped it sooner, she railed.

You speak as if he’s fifteen, I cruelly observed. The odds were he’d fall in love sooner or later. Inspired by snark I added, no amount of mummy-wife control can prevent people falling in love. He broke the rules, didn’t he? He could no longer tell you, she meant nothing to me.

Take responsibility for your decision to live as the owner/manager of another adult being, I finally shouted. For what that decision has done to your life. For how it has brought you to this, yelling at me, telling me you are waiting for me to die, threatening me you’ll devise some silencing punishment.You think you can stop me writing whatever I want? You do? You just fucking well try.

And don’t blame me for your unfortunate life choices. Sister.

ƒ

He told me if he lost me he would never write again. You will, he said, but I never will.

No, I protested, no, why would you think that, no!

He sadly shook his head.

And then he kissed the inside of my wrist.

Your skin, he said. Your softness. Your soft, beautiful skin.

ƒ

Do you love me still? he asked after a bruising argument. In spite of everything?

I love you still, I told him. In spite of everything.

As a grieving friend of Arnie’s I find it hard to express how happy I feel to know that while he was stuck there in that awful place that the stroke took him that you were by his side. I tried to be a regular comforting visitor but the timing was bad, I was imprisoned by a long bout of debilitating chronic depression the likes of which I hope to never feel again. When the right drugs finally kicked in I searched for but couldn’t find him. Nobody told me when he died. Will you contact me to talk? Gail.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gail, I’ve left a message on your blog with my email but here it is again: noplaceforsheep@outlook.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such tardy replies. I’m very sorry to take so long to look in the right place for your reply/replies. I’m ripping into your blog which is addictive so I can’t leave it alone.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Gail, Please can you use my email noplaceforsheep@outlook.com and we can arrange contact?

Thank you. Jennifer

LikeLike

Gail, I don’t know how t contact you but if you email me at noplaceforsheep@outlook.com we can talk

LikeLike