David said, You are a sex goddess. You are perfect for me.

Silence was my reaction to what he thought to be a compliment. No woman with a modicum of sense wants to be on a pedestal from which she can only fall. Fulfilling another’s excessive expectations is a mug’s game. So I stared at him while imaging myself with winged heels wearing a filmy frock, flying off with a sly glance over my shoulder, smiling about what I knew and he didn’t.

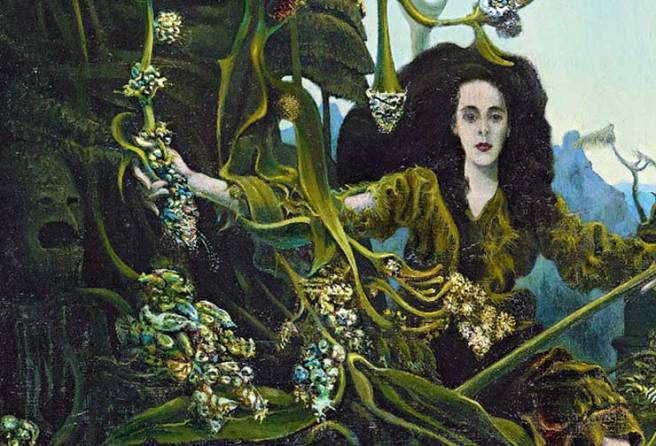

Goddesses don’t hang about with mortals. They drop in, give them a taste of eternity, make their lives miserable with a glimpse of how perfect things could be, but aren’t.

His hunger showed itself to me. Then desperation made its appearance. Together, they filled his eyes. I watched as they colonised his being. He quivered. He became fearful. What is this, he whispered, as if he expected me to know.

I felt my usual confusion settling in. The confusion that takes over when a situation doesn’t feel right, but I’m too apprehensive about what might happen if I try to change it.

He was dying of cancer, he’d told me. He’d been granted a reprieve, but he didn’t expect that it would last. He wanted a chance to know what he’d never yet known. Sensuality. The transgression of sexual boundaries. Fulfilment, before he died.

If I was a goddess, I’d know how to refuse a dying man.

I am visiting Alison in her nursing home. Alison is my substitute mother. When Jane (who is her real daughter) and I arrive, Alison is in her wheelchair in the day room. The television is on. Kamal, an entertainer whose existence I had forgotten, is singing Jerusalem. He wears a gold kaftan that shimmers when the lights touch on him. His teeth are blindingly white. I stand beside Alison’s wheelchair, staring at the television. William Blake, I say. This song, it’s from a poem by William Blake. Nobody hears. Kamal’s belting out the last hosannas. He’s backed by a full orchestra and a choir wearing Santa hats.

His next song is Old Man River for which he has a change of costume: sequined waistcoat over diamante-encrusted collarless shirt. When he gets to the line “I’m tired of living and scared of dying” I remark how well it expresses the ambience in this day room. Then the combination of William Blake and the nursing home make me remember my husband, who loved the first, and died of a stroke in the second.

My husband never called me a sex goddess, but he did dream I was a helicopter pilot and he was my passenger. I was a very good pilot, he told me, and he felt no fear.

The goddess of sex is, of course, Aphrodite. Born from sea-foam, carried naked to the shore in a shell, she is infinitely desirable and desiring. Whenever she bathes in the sea her virginity is restored to her, and so with every lover it is as if he is her first. I understand this metaphorically. I know there are men who desire virginity, and it was men who wrote Aphrodite’s story.

Firsts mattered to David. The first time he had felt this. The first time he had done that. Best of all, the first time we. My desire for you is infinite, he wrote. These firsts are part of the richness of our relationship, he wrote.

But in the moment I was more helicopter pilot than goddess, and I didn’t believe him.

Do you think I’m addicted to sex, David asked. The question startled me. I have no idea, I said. Did somebody tell you that? He didn’t answer. He looked beaten, and sad.

A helicopter pilot would be able to work it out. A goddess wouldn’t care. I don’t care. It’s tedious, the habit of amateur diagnosis. I look up the symptoms. of sex addiction. Hmmm. Maybe there’s a few that fit. So what?

You touch me so gently, he says. He doesn’t touch me gently. He falls on my breasts and suckles like a starving baby, kneading and pressing as if to make the imagined milk flow faster. He moans as he sucks. Goddess-like, I stroke his head, bare from treatment, later to be replaced by a silky tonsure.

In Alison’s day room, Kamal is bringing things to an end with My Way. I roll my eyes at Jane as we sit either side of the wheelchair. Alison has nodded off. She does this, disconcertingly, in the middle of a meal or a conversation then comes back to whatever she was doing as if she’d never left. I’m struggling not to think of my husband but there’s a man sitting close by with post-stroke symptoms, speechless and one side of his body limp.

The world is still strange without us in it, I tell my husband that night. There’s just me, and the other part of us will be absent for evermore.

I will pin love inside your coat, and leave unlocked the garden gate*

I will love you infinitely, I said at our wedding.

This is proving to be true.

*Kate McGarrigle, I cried for us